So many people have told me how strong I am. I do not always feel strong.

What does it mean to be strong? My parents recently traveled to Scotland and discovered that our family name is connected to the MacLeod clan, whose motto is “Hold Fast.” That seems, at least at first, a reasonable way of thinking about strength: holding fast, holding tight, holding on. When people ask me how I am doing, I often find myself resorting to a more casual expression of the same idea: “hanging in.” “Strength,” for most I think, tends to call up ideas of persistence, toughness, control, perseverance.

But I have felt strongest, and most at peace, in moments of letting go.

Not long after my initial diagnosis, when I was really reeling, a former student of mine, Carrie, sent me some wise, encouraging words. She wrote, “You’re one of the strongest people I have ever met. Strength doesn’t mean you can’t be mad, that you won’t cry, and that you won’t break down. All of those are forms of strength.” They don’t sound that way, at first. They sound like losing it. But in reality control was never mine to lose. And each of these responses is a form of letting go.

In the past few months, I’ve seen several videos titled something along the lines of “How Heavy is Your Glass of Water?” circulating around Facebook. My preferred version, by Knowable Studio, is “Remember to put your glass down.” The message in each is the same: a psychologist, speaking to an audience about stress, holds up a glass of water and asks how heavy it is. She goes on to make the point that its absolute weight is irrelevant. The longer one holds it, the heavier it feels, the harder it becomes to function. The same is true with stress and suffering in our lives. The lesson: remember to put the glass down.

So I have found my own ritual way of setting the glass down, a physical as well as mental process. I prefer to find a place outside and sit or kneel on the ground, hands open to the sky, my heart lifted, my eyes closed. Then I have a short conversation with the universe.

The first time I engaged in this ritual was almost accidental. It was our first evening on Folly Beach, when we were still waiting on some significant test results. I went for a sunset walk on the beach, collecting several Tellin clams and jingle shells along the way. Stopping to watch the light change as the sun dropping behind me reflected off and outlined a bank of clouds gathered over the ocean, I sank to the sand, facing the horizon, and spread my treasures on the beach before me. I told the universe and its various representatives that I needed to give this weight to them: Universe, God, Goddess, Jesus, Buddha, all that is that is greater than my knowledge and understanding, all that is that is Love in this world, I need to give this to you, because I cannot carry it. It is too much for me. I sat in silence for a few minutes, shed a few quiet tears, then rose and walked back up the beach, leaving my shell offering. I felt a distinct lightness, a sense of renewed peace.

I’ve repeated a similar ritual since. Once is not enough; it’s too easy to begin grasping and gripping and holding on tight. Letting go requires practice. Letting go is scary, largely because it does mean giving up the illusion of control.

Sometimes I fear letting go, because I’m afraid it sounds, or feels, like giving up. Accepting I cannot control all that comes, saying I’ll embrace whatever happens, whether it’s what I want to happen or not, feels a little like giving the universe permission to do its worst. Maybe if I just hold on and worry over all the details and possibilities, a little voice in my head says, it will better prepare me, even prevent a bad outcome. Of course, that’s balderdash. Letting go does not mean surrendering my desire for health or long life. It’s simply an acknowledgment that I can hold on as tightly as I want to a desired outcome, but there are no guarantees. And there is power, peace, and strength in accepting that truth.

I remind myself of this fact as we anticipate the next appointments, the next pieces in the process: first, follow-up imaging, post-chemotherapy, to see how much the treatment shrank the cancer, and then my surgery consultation. I confess I’m bracing myself; thus far, outside the “no metastasis” declaration, the news has always been worse than we’d hoped: you want them to say the lump is benign, but it’s cancer; you want them to say it’s Stage 1, but it’s Stage 3. It’s strange, how you can find ways to keep shifting the barometer of what you can accept: I can deal with X as long as not Y, Y as long as not Z. The internal bargaining is exhausting and doesn’t accomplish much. I know I’ll fare better if I can let go of my ideas about what should be and meet myself and the world where we are.

Perhaps I’ve been driven to seek my strength, the solace of letting go, outside on the sand, or under the trees, by the same impulse poet Wendell Berry renders so beautifully in “The Peace of Wild Things”:

When despair for the world grows in me

and I wake in the night at the least sound

in fear of what my life and my children’s lives may be,

I go and lie down where the wood drake

rests in his beauty on the water, and the great heron feeds.

I come into the peace of wild things

who do not tax their lives with forethought

of grief. I come into the presence of still water.

And I feel above me the day-blind stars

waiting with their light. For a time

I rest in the grace of the world, and am free.

That evening on Folly Island, as I made my way back to our beach house, I paused to sit again on one of the large jetty boulders closest to our rental. When I looked down, a single olive shell rested in a cup of the rock at my feet. I reached down to pick it up, recalling that the very first time I’d told my now-husband Steve I loved him, I’d done so on a trip to the beach, by placing an olive shell I’d found on his pillow.

Was this new olive shell a message? A portent? I don’t know. I hold on to it as reminder to keep letting go. It tells me the peace of wild things is with me, and that is enough.

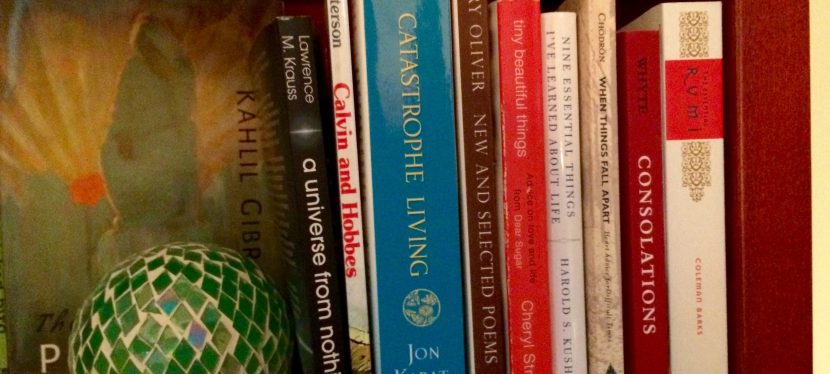

The book is subtitled “Advice on love and life from Dear Sugar,” but to label Tiny Beautiful Things as merely a collection of advice columns does not do justice to its beauty or wisdom. Strayed turns the conventions of advice columns upside down and taps into her own memories and experiences in her responses, doing “something brilliantly counter-intuitive,” as noted by the Public’s Artistic Director Oskar Eustis,” using self-revealing stories of her own life for generous purposes.” Strayed’s luminous and powerful responses to what are often heart-wrenching letters are some of the most lucid, honest, moving essays I have ever read.

The book is subtitled “Advice on love and life from Dear Sugar,” but to label Tiny Beautiful Things as merely a collection of advice columns does not do justice to its beauty or wisdom. Strayed turns the conventions of advice columns upside down and taps into her own memories and experiences in her responses, doing “something brilliantly counter-intuitive,” as noted by the Public’s Artistic Director Oskar Eustis,” using self-revealing stories of her own life for generous purposes.” Strayed’s luminous and powerful responses to what are often heart-wrenching letters are some of the most lucid, honest, moving essays I have ever read. My heart buoys and breaks over different matters these days, but Strayed’s words still speak to me. Gauging by the shared laughter and the unmistakable sounds of whole-audience-weeping in the theatre, they speak to many. (When the lights came up, Steve turned to me, both of us still wiping our eyes, and he said, “You didn’t warn me!”) It was a powerful performance.

My heart buoys and breaks over different matters these days, but Strayed’s words still speak to me. Gauging by the shared laughter and the unmistakable sounds of whole-audience-weeping in the theatre, they speak to many. (When the lights came up, Steve turned to me, both of us still wiping our eyes, and he said, “You didn’t warn me!”) It was a powerful performance. And this, in response to a professor and class who asked Sugar’s advice to graduating college students: “Whatever happens to you belongs to you. Make it yours. Feed it to yourself even if it feels impossible to swallow. Let it nurture you, because it will.” (133)

And this, in response to a professor and class who asked Sugar’s advice to graduating college students: “Whatever happens to you belongs to you. Make it yours. Feed it to yourself even if it feels impossible to swallow. Let it nurture you, because it will.” (133)

There’s an article that’s made its way around the internet about the

There’s an article that’s made its way around the internet about the

I’m looking forward to experiencing that revelation again, whenever it finally arrives. I know it might be a while. Until then, I try to remember what my friend Sarah said when I shared my frustrations with her about my lack of productivity, my inability to do all the things I need and want to do.

I’m looking forward to experiencing that revelation again, whenever it finally arrives. I know it might be a while. Until then, I try to remember what my friend Sarah said when I shared my frustrations with her about my lack of productivity, my inability to do all the things I need and want to do.

Still, as surgery looms on the horizon, I’ve grown more aware of how the language of aggression, while ostensibly empowering, also pits one against one’s own body in some curious and distressing ways. My sister-in-law Lisa, a survivor, mentioned her discomfort with this language shortly after I was diagnosed. Susan Sontag, in a 1978 essay entitled “Illness as Metaphor,” describes the dilemma: “The controlling metaphors in descriptions of cancer are, in fact, drawn…from the language of warfare; every physician and every attentive patient is familiar with, if perhaps inured to, this military terminology. Thus, cancer cells do not simply multiply; they are ‘invasive’” (714). The language surrounding treatment has a similar inflection: chemotherapy is “chemical warfare, using poisons” that aim to “kill” (715).

Still, as surgery looms on the horizon, I’ve grown more aware of how the language of aggression, while ostensibly empowering, also pits one against one’s own body in some curious and distressing ways. My sister-in-law Lisa, a survivor, mentioned her discomfort with this language shortly after I was diagnosed. Susan Sontag, in a 1978 essay entitled “Illness as Metaphor,” describes the dilemma: “The controlling metaphors in descriptions of cancer are, in fact, drawn…from the language of warfare; every physician and every attentive patient is familiar with, if perhaps inured to, this military terminology. Thus, cancer cells do not simply multiply; they are ‘invasive’” (714). The language surrounding treatment has a similar inflection: chemotherapy is “chemical warfare, using poisons” that aim to “kill” (715).

The main reason I resist is that none of us knows the future. That’s a fundamental truth. It isn’t that I don’t want to be healthy and cured—of course I do! But it feels like tempting fate to declare certainty in relation to a particular outcome; I don’t and can’t make predictions. I can only know the present.

The main reason I resist is that none of us knows the future. That’s a fundamental truth. It isn’t that I don’t want to be healthy and cured—of course I do! But it feels like tempting fate to declare certainty in relation to a particular outcome; I don’t and can’t make predictions. I can only know the present. If this is my life (and it is) and if my life (like all our lives) is finite, and if I don’t know its deadline (and none of us does), then how do I want to spend it? Waiting and wishing for a different kind of life, a different kind of day, a “better” one in some projected future? Or do I find a way to accept where I am in the present, since that’s all any of us really knows or has?

If this is my life (and it is) and if my life (like all our lives) is finite, and if I don’t know its deadline (and none of us does), then how do I want to spend it? Waiting and wishing for a different kind of life, a different kind of day, a “better” one in some projected future? Or do I find a way to accept where I am in the present, since that’s all any of us really knows or has? Kushner’s work is embedded in the Jewish faith, though his lessons are broadly applicable, drawing equally upon everyday people’s stories as well as religious texts and history for illustration. I’m a spiritual seeker who does not identify solely or specifically with any single faith tradition at this point in my life, though I feel there is something larger and greater than individual human desires, and I tend to imagine the sacred, in the broadest terms, as the realization of the combined forces of love and compassion in the world. So much of Kushner’s understanding of who and what “God” is (and isn’t) resonates with me, given that one of his truths is “God is Not a Man Who Lives in the Sky.” He writes, “To me, God is like love, affecting all people but affecting each one differently, according to who he or she is. God is like courage, a single trait that manifests itself differently as it is filtered through the lives and souls of specific individuals” (29). Love and courage: both profoundly human and deeply sacred.

Kushner’s work is embedded in the Jewish faith, though his lessons are broadly applicable, drawing equally upon everyday people’s stories as well as religious texts and history for illustration. I’m a spiritual seeker who does not identify solely or specifically with any single faith tradition at this point in my life, though I feel there is something larger and greater than individual human desires, and I tend to imagine the sacred, in the broadest terms, as the realization of the combined forces of love and compassion in the world. So much of Kushner’s understanding of who and what “God” is (and isn’t) resonates with me, given that one of his truths is “God is Not a Man Who Lives in the Sky.” He writes, “To me, God is like love, affecting all people but affecting each one differently, according to who he or she is. God is like courage, a single trait that manifests itself differently as it is filtered through the lives and souls of specific individuals” (29). Love and courage: both profoundly human and deeply sacred. In the later chapter on doubt and anger, Kushner explores another theme close to my heart, especially at this juncture in my life. I have always been a bit allergic to certainty, and he actively embraces the idea that we should raise questions, “admit our anger” when it arises, and affirm a “readiness to live with doubt.” To do otherwise means we’re avoiding truth and minimizing the complexity of any genuine relationship: “Accepting anger, ours and that of people close to us, has to be part of any honest relationship” (130), writes Kushner, and it’s only through acknowledging that the tough stuff is equally as valid as the good that we can love–that we can be fully present in any capacity, I would add–with our whole hearts.

In the later chapter on doubt and anger, Kushner explores another theme close to my heart, especially at this juncture in my life. I have always been a bit allergic to certainty, and he actively embraces the idea that we should raise questions, “admit our anger” when it arises, and affirm a “readiness to live with doubt.” To do otherwise means we’re avoiding truth and minimizing the complexity of any genuine relationship: “Accepting anger, ours and that of people close to us, has to be part of any honest relationship” (130), writes Kushner, and it’s only through acknowledging that the tough stuff is equally as valid as the good that we can love–that we can be fully present in any capacity, I would add–with our whole hearts.

Public support and awareness is a good thing, of course. Our local mall recently hosted a “Positively Pink Parade,” raising funds for the Every Woman’s Life program, which provides free mammograms to low-income, uninsured, and underinsured women in our area. Personally, I had the opportunity to attend a retreat for breast cancer survivors sponsored by our local breast care center. It was a powerful experience, both uplifting and draining, physically and emotionally. We interacted with other survivors, created healing art, asked questions of a panel of doctors. It was humbling and inspiring to hear the stories and witness the resilience of the women gathered there, several of whom referred to our shared experience as a kind of sisterhood.

Public support and awareness is a good thing, of course. Our local mall recently hosted a “Positively Pink Parade,” raising funds for the Every Woman’s Life program, which provides free mammograms to low-income, uninsured, and underinsured women in our area. Personally, I had the opportunity to attend a retreat for breast cancer survivors sponsored by our local breast care center. It was a powerful experience, both uplifting and draining, physically and emotionally. We interacted with other survivors, created healing art, asked questions of a panel of doctors. It was humbling and inspiring to hear the stories and witness the resilience of the women gathered there, several of whom referred to our shared experience as a kind of sisterhood.